Class III Malocclusion Surgery: When to Perform Only Mandibular Surgery?

Maschinenübersetzung

Der Originalartikel ist in ES Sprache (Link zum Lesen) geschrieben.

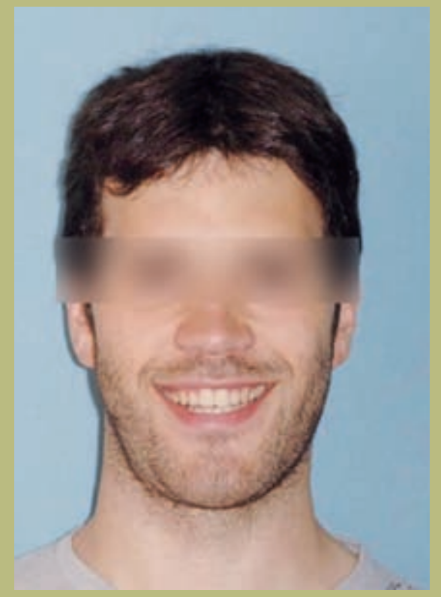

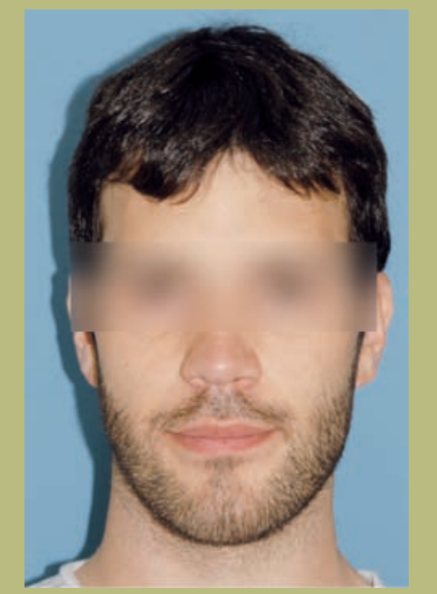

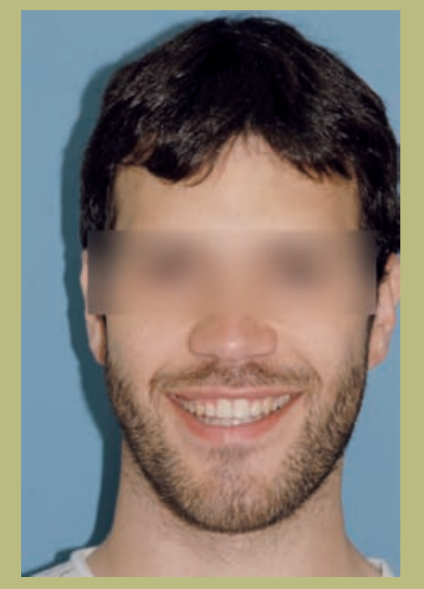

Anamnesis

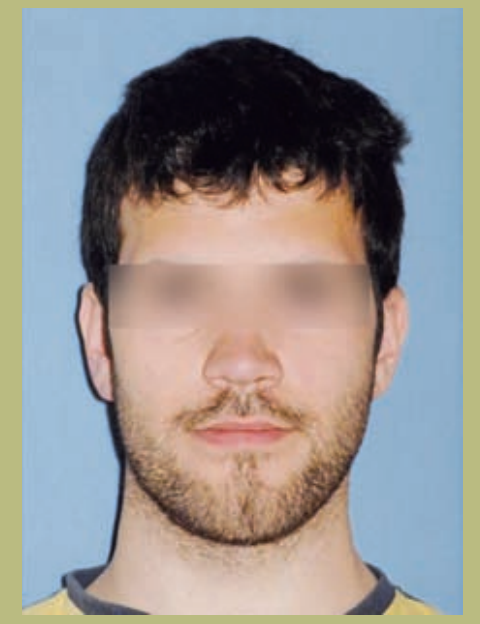

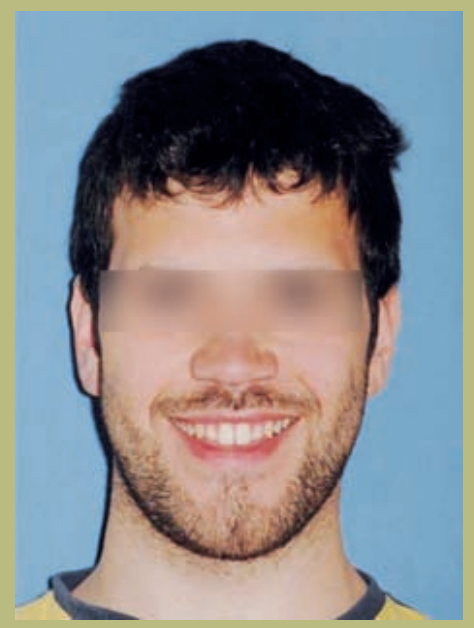

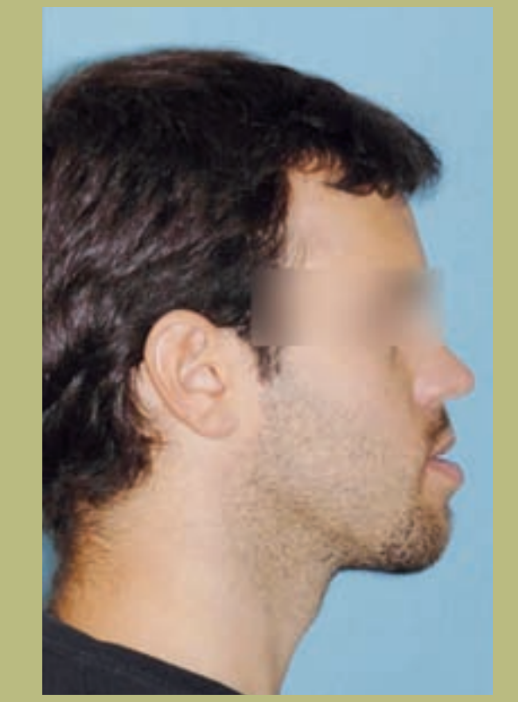

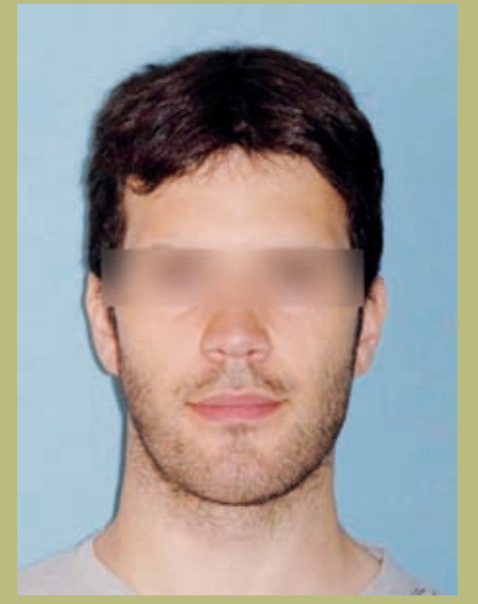

The 26-year-old patient came to the consultation for surgical treatment of his mandibular deformity. The patient complained of a large jaw and discomfort in the left temporomandibular joint.

Facial analysis

- Forehead (figures 1 and 2)

- Slight exposure of the sclera.

- Normal bicigomatic width.

- Flat paranasal configuration (hypoplasia of paranasal areas).

- The nostrils and interalar distance are widened.

- Slight mandibular asymmetry.

- Long face with a feeling of increased verticality of the chin.

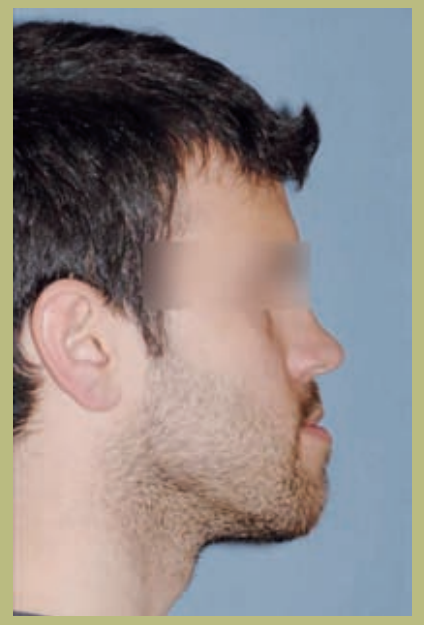

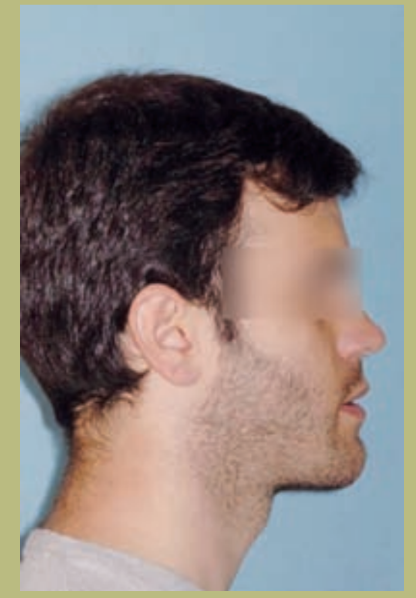

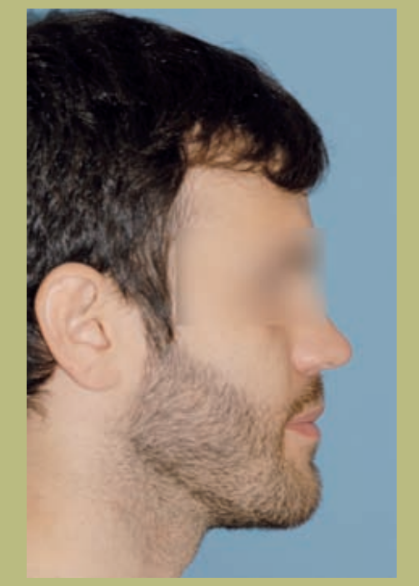

Profile (figure 3)

- Decreased infraorbital rim projection.

- Flat cheek configuration.

- Flat paranasal configuration.

- Normal nose size with slightly increased nasolabial angle.

- Increased cervico-mental length.

- Normal cervico-mental angle.

- Decreased mentolabial groove.

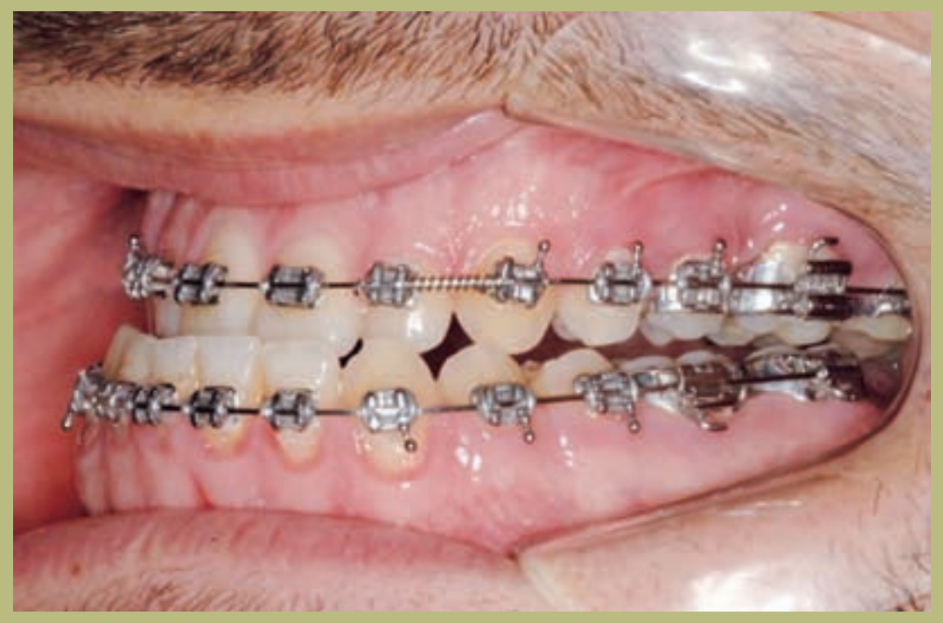

Intraoral analysis (figures 4–8)

- Class III molar and canine complete right and left.

- Anterior crossbite with an overjet of -7 mm.

- Overbite 2 mm.

- Rotation 16, 26, 25.

- Deviation of the lower midline to the right by 1.5 mm.

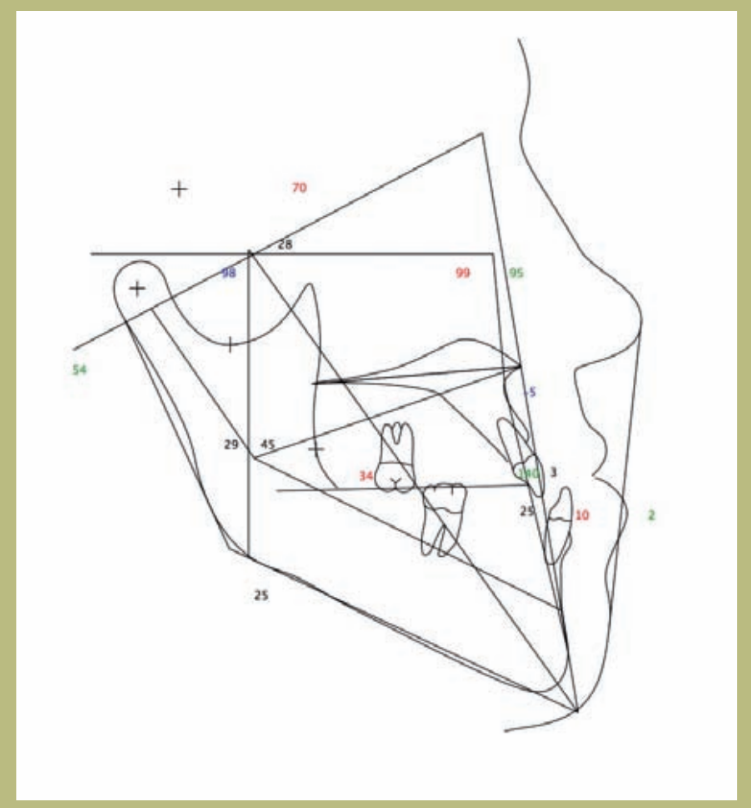

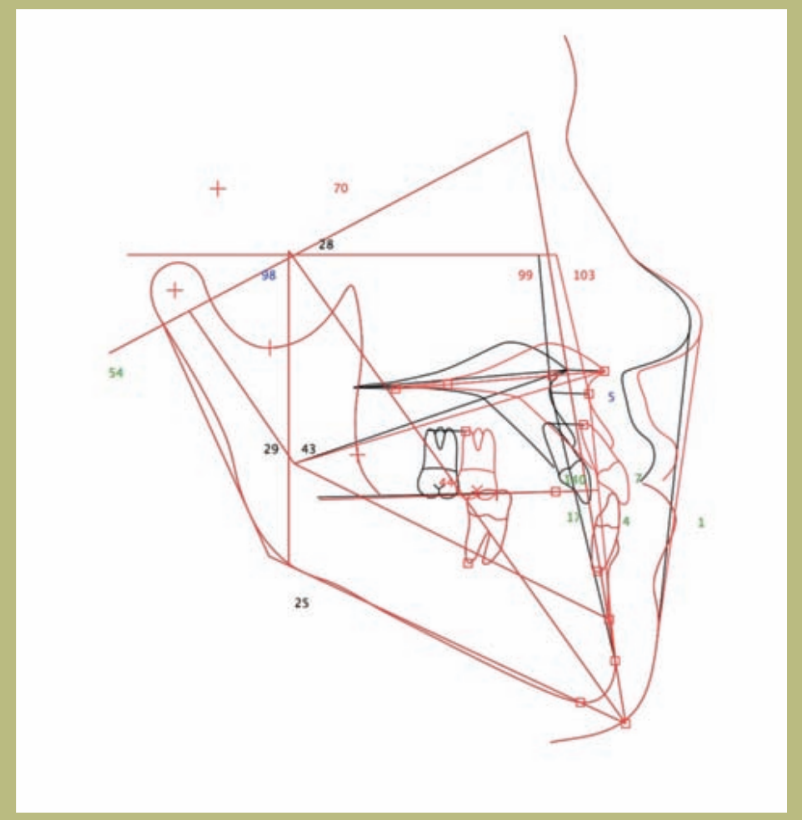

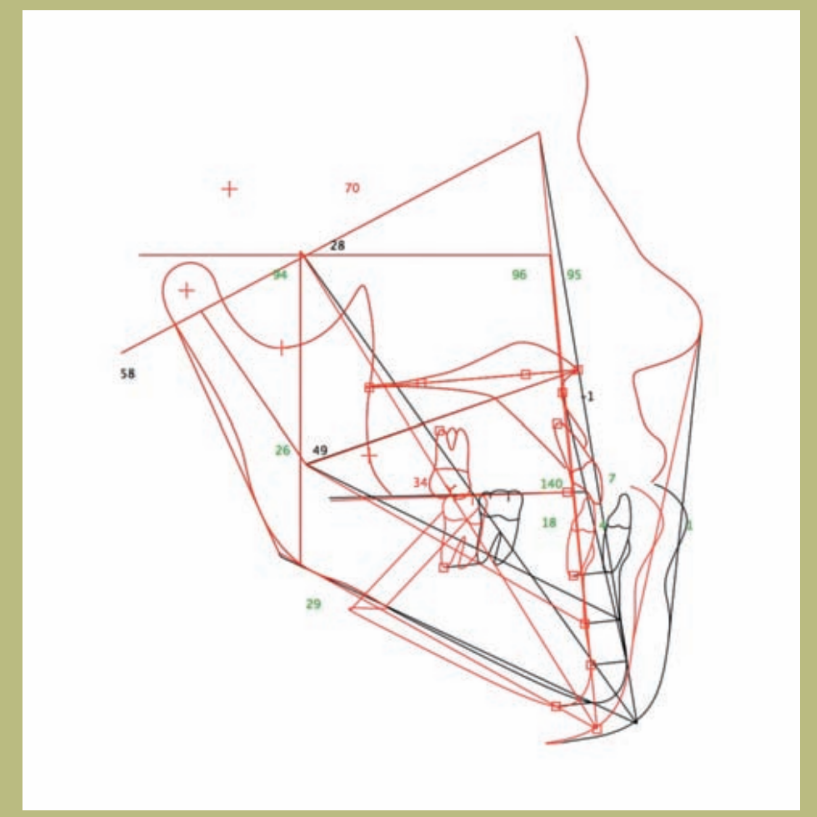

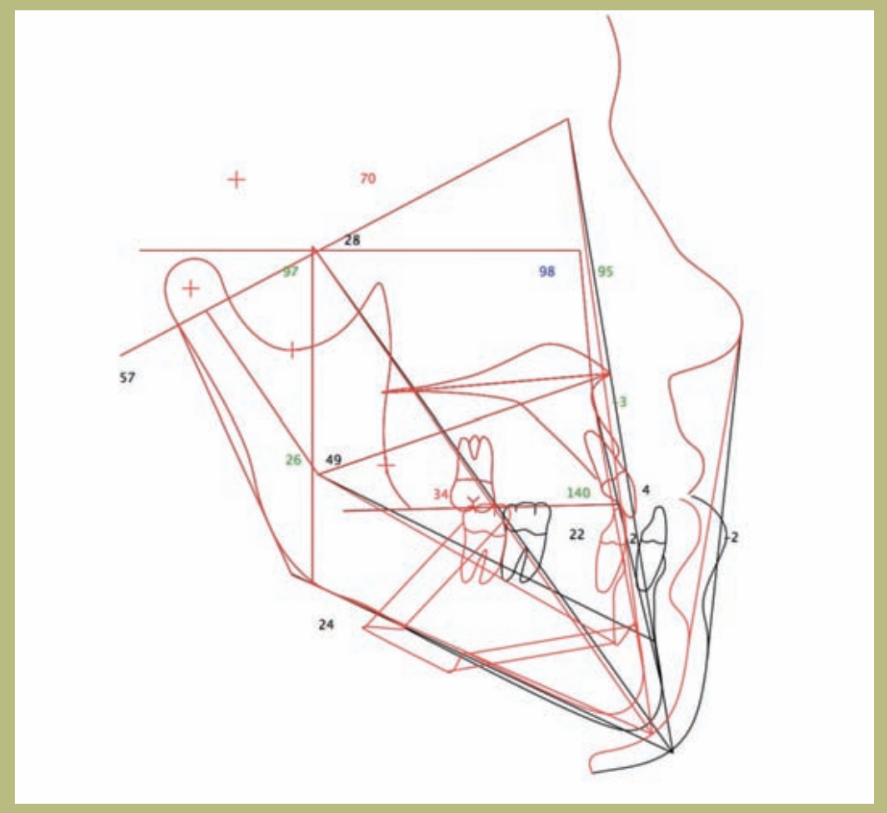

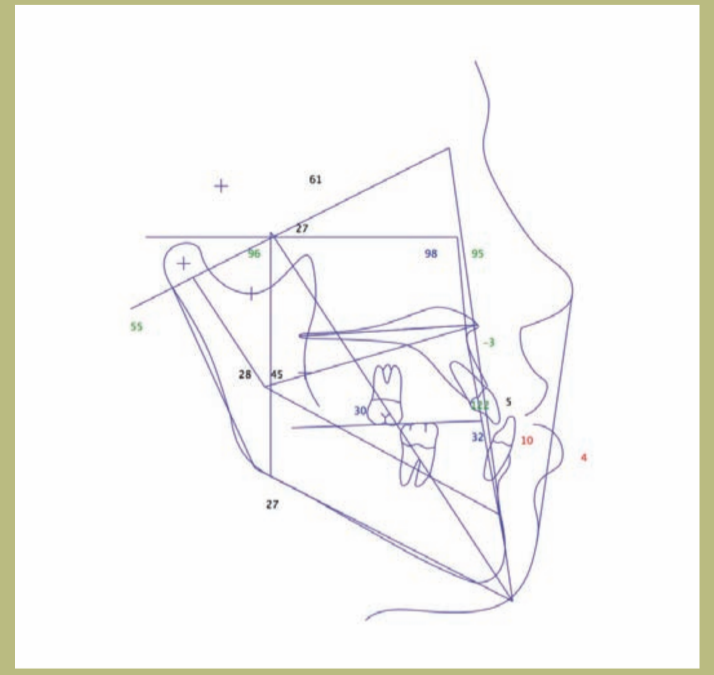

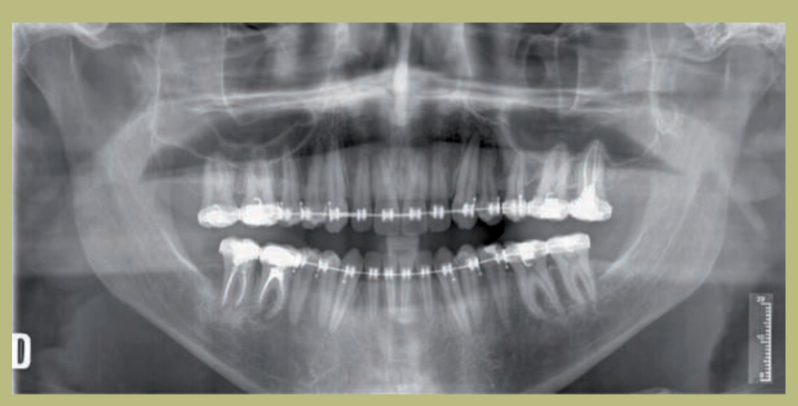

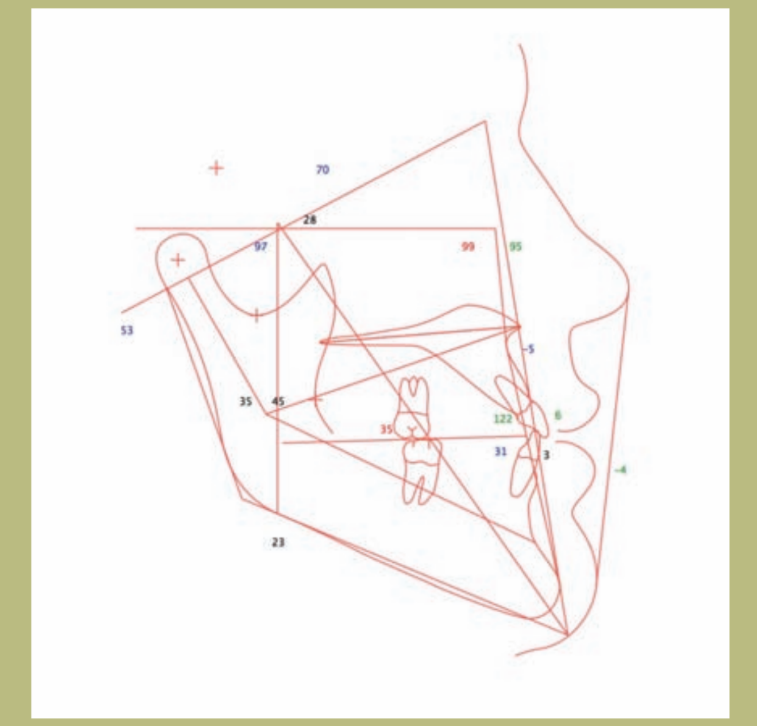

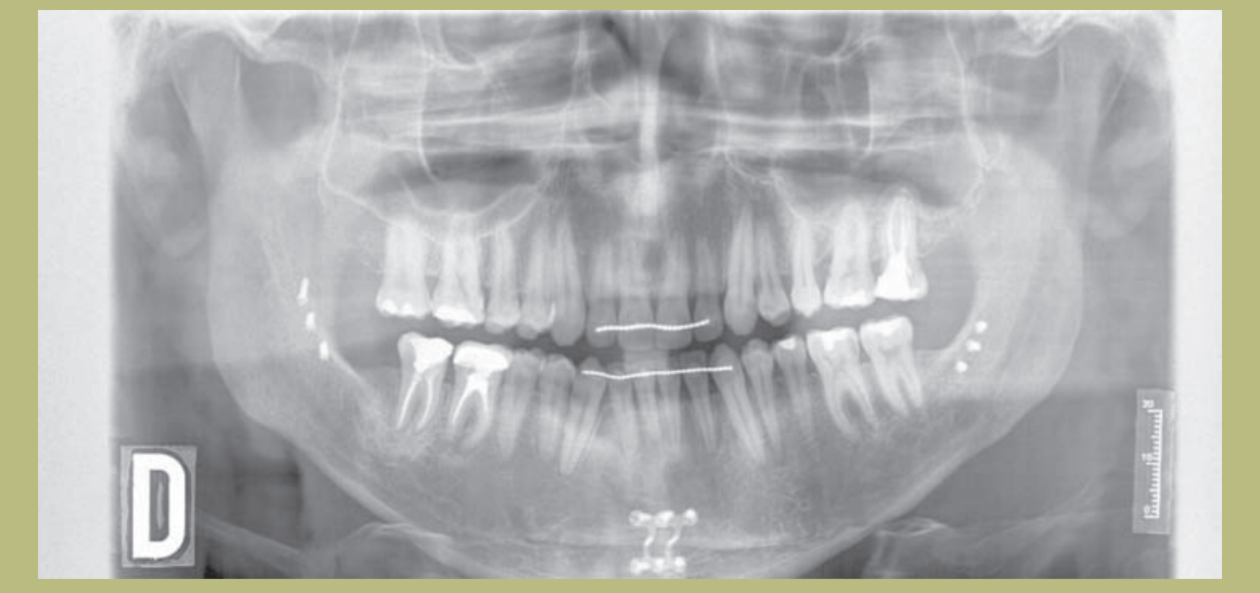

Radiological analysis (figures 9–11)

1) Orthopantomography:

- Angular bone defect of the 26.

- Extrusion of the 17.

2) Cephalometry:

- Class III skeletal of mixed origin (maxillary hypoplasia and mandibular hyperplasia).

- Upper incisors correctly positioned over their bony bases and the lower ones slightly lingualized.

V.T.O. (figures 12–14)

1) If only a maxillary advancement is performed, several potential problems arise. On one hand, the advancement is very large (10 mm) and, on the other, it would have a very unfavorable effect on the nose and its pedestal, resulting in a very open nasolabial angle (greater than 105 degrees), and a widening of the alar base that would be difficult to manage surgically; moreover, it would decrease the thickness of the upper lip and increase the exposure of the upper incisors. Finally, it would worsen the malar deficiency that could be compensated with the placement of malar prostheses.

2) If only a mandibular retrusion were undertaken, there would be a loss of support of the soft tissues of the mandible with the appearance of an obtuse cervico-mental angle and double chin.

3) If mandibular retrusion surgery and mentoplasty were combined, it would allow the cervico-mental angle to remain unaltered and prevent the appearance of a double chin, with the added advantage of improving the mentolabial sulcus.

Pre-surgical orthodontic objectives (figures 15–25)

1. Maintain the width of the arches, as the crossbite observed is due to the different sagittal position of the maxilla in relation to the mandible; however, it disappears when placing the models in class I.

2. Eliminate the dento-alveolar compensations by correctly placing the incisors over their bony bases, that is, increasing the torque of both the upper and lower incisors.

3. Maintain the deviation of the midline, as it is due to a skeletal asymmetry that will be corrected in surgery.

During the course of pre-surgical orthodontics, a progressive sequence of arches was followed: 016 thermal niti, 018 thermal niti, 19x25 thermal niti, and 19x25 steel.

Some lower incisor brackets were recemented to achieve proper alignment. After three months of having the steel arches, complete pre-surgical records were made using radiographs, photographs, and model mounting on an articulator. Based on these records, a final S.T.O. was performed, and the final surgical movements of mandibular retrusion and mentoplasty were decided for the reasons previously stated.

A few days before the surgery, posts were placed in the arches to use them as support for the intermaxillary elastics.

Preoperative planning

In the preoperative planning, a facial aesthetic study was conducted with lateral cephalometric analysis and dental models that were mounted on the articulator to plan the details of the surgery. The models were mounted on a semi-adjustable articulator in centric relation one week before the surgery. An inverted overjet of 7 mm was confirmed.

A mandibular setback surgery was planned to achieve a functional and aesthetic occlusion of 9 mm, and a sliding osteotomy of the chin or advancement genioplasty of 7 mm and vertical reduction of 2 mm.

The decision for mentoplasty is based on aesthetic criteria to avoid losing support of the skin envelope of the lower third of the face, not altering the cervicomandibular angle, and by decreasing the height and advancing the chin, improving the labiomentoniano angle.

Surgery

Under general anesthesia, nasotracheal intubation was performed. The incision lines in the mandibular area and in the chin were infiltrated with a solution of lidocaine with 0.25% and saline with adrenaline at 1/100,000; the ramus osteotomies were performed with an Osteomed oscillating saw, starting with the horizontal cut in the ramus and finally with the vertical cut in the mandibular body.

At all times, the cut was made on the outermost part of the mandible, immediately medial to the external cortical and external oblique crest. Once the osteotomy was completed and the integrity of the vascular-nervous bundle was analyzed, the distal fragment was positioned in the previously made acrylic splint and intermaxillary wiring was performed. A fragment of bone was removed from the anterior end of the proximal fragment or condyle, to avoid interference with the backward movement of the mandibular body of 1 cm. The osteotomy was fixed with a total of 3 bicortical screws on the external oblique crest; then, the passive fit of the mandible was checked, observing an adequate condylar position.

Subsequently, an incision was made in the vestibule in the symphyseal area, exposing the chin and both dental nerves; after marking the midline, the chin was cut with an oscillating saw and once the osteotomy was completed, the chin advanced freely and, thanks to the design of the osteotomy –oblique and inferior towards the back–, 3 mm of height was lost, resulting in a more harmonious labiomentonian angle.

Genioplasty was rigidly fixed with Osteomed® plates and four screws. Closure was performed with 2 layers to prevent chin ptosis.

Post-surgical Orthodontics (figures 26-36)

Starting at 6 weeks, a correct occlusion was established using elastics to settle the occlusion and combat relapse.

Discussion (figures 37–42)

The surgical correction of prognathism has traditionally involved the posterior repositioning of the mandibular body with ramus osteotomies. This approach is based on cephalometric studies and has produced predictable and favorable occlusal and functional outcomes. Frequently, this approach to malocclusion and skeletal disharmony was resolved at the expense of facial aesthetics, resulting in loss of projection of the maxillofacial skeleton and loss of support of the facial soft tissues. The loss of skeletal support and volume results in increased laxity, deepening of wrinkles, a tendency towards a more obtuse cervicomandibular angle, and an increase in the double chin.

Maxillary advancement establishes a normal occlusion producing skeletal expansion and extending the envelope. However, in this case and contrary to the prevailing treatment philosophy, only mandibular surgery was decided upon, based on the following facial analysis:

- Very open nasolabial angle.

- Insufficient nasal dorsum for the anthropometric characteristics of this case.

- Feeling of prognathism with exaggerated anterior divergence and appearance of a large mandibular body.

- Macrogenia or excessively long chin vertically. In this case, any type of maxillary advancement would have resulted in excessive projection of the nasal pedestal – further increasing the nasolabial angle – and projection of the tip, resulting in a saddle nose appearance that would require difficult subsequent nasal surgery.

The patient was offered an increase of the malar and maxilla with prosthetics which was rejected. The mandibular setback surgery of 9 mm poses two potential complications:

- Recurrence.

- Loss of soft tissue support of the lower facial third and deterioration of the cervicomandibular angle.

The loss of support of the skin envelope was resolved through an advancement and vertical reduction mentoplasty that redistributed the soft tissues, improved the labiomentonian angle, and did not result in alteration of the cervicomandibular angle with an increase in the double chin. Mandibular setback surgery, along with maxillary descent and transverse expansion of the maxilla, are the most unstable, unpredictable, and recurrent movements in orthognathic surgery.

In general circumstances, mandibular setback is predictable if skeletal stabilization is ensured with plates and/or screws in all osteotomies with or without fixation of a prefabricated splint, which is connected with wires to the brackets of the maxilla that has not been mobilized, if the magnitude is less than 7 mm. In these cases, if there is early malocclusion after surgery, it is due to an intraoperative technical error.

In the later relapse, orthodontic factors such as a lack of elimination of dental compensations influence; or in the management of transverse discrepancies or surgical factors, such as inadequate intraoperative condylar positioning, rotation and loss of control of the proximal ramus fragment after fixing it to the distal in the desired occlusion, insufficient mobilization of the fragments, outward rotation of the condyle from the glenoid fossa or insufficient fixation of the osteotomies; and, in many cases, especially in males, undiagnosed condylar hyperplasias or patients who have not completed growth.

In our patient, special care was taken to achieve passive fixation with the condyles in their place in the glenoid cavity, without torsions, and that upon removing 1 cm of bone fragment there were no interferences in the position of both osteotomies. The centric relation was checked multiple times in the operating room and soft class

III elastics were placed. Our experience in class III with bicortical screws is highly satisfactory, providing a high degree of stability with a minimum of screws in the mandible.

César Colmenero Ruiz, Fe Serrano Madrigal, Javier Prieto Serrano

Bibliography

- Rosen HM. Maxillary advancement for mandibular prognathism: indications and rationale. Plast Reconstr Surg 87: 823-831, 1991.

- Epker B, Fisch I. The surgical-orthodontic correction of class III skeletal open bite. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 73: 601-617, 1978.

- Kobayashi T, Hoshima T. Masticatory function in patients with mandibular prognathism before and after orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51: 997-1004, 1993.

- Proffit Wr, Philips C, Dann C. Stability after surgical orthodontic correction of skeletal class III. Int. J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg 6: 7-14, 1991.

- Obwegeser HL. Mandibular growth anomalies. Springer-Verlag: 332-335, 2000.

- Spiessl B. The sagittal splitting osteotomy for correction of mandibular prognathism. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 9: 496-502, 1982.

- Rosen HM. Aesthetic guidelines and refinements in genioplasty: the role of the labiomental fold. Plast Reconstr Surg 88: 5, 14, 1991.

- Wolfe SA. Shortening and lengthening the chin. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 15: 223-228, 1987